Some of the most important innovations in electronic music came about by mistake. Whether it be the way that Roland’s TR-808 and then the TR-909 drum machines were picked up and abused by early techno and electro producers, the emergence of the Fairlight sampler, or the accidental advent of quantisation or the Moog’s filter sound, unintentional discoveries about aspects of certain equipment have had a profound impact on the growth of electronic music. Of course, these developments wouldn’t have happened if certain pioneers hadn’t explored the accidental path they had been sent down. Over the coming pages, DJ Mag looks at the happy accidents that have led to some of the most familiar sounds and kit in our music today…

WORDS: Declan McGlynn

Experimentation has always been at the heart of electronic music. Pushing our tools to the limit, wiring them in ways they were never intended or twisting software to spit out unexpected results, electronic music thrives on controlled chaos. Often, it results in a whole new sound that goes on to define a track, an artist or even a genre.

But it’s not just the sonic innovators in the studio who’ve benefited from the unpredictable nature of experimentation. Throughout history, some of the most iconic gear that went on to inspire the most iconic music began life as a humble accident. So often in electronic music, it’s the unintended results that reap the biggest rewards.

That’s not to say these innovations were pure chance — in the same way that luck finds those who work the hardest, it was the determination of legends like the father of synths Dr Bob Moog, Linndrum and MPC designer Roger Linn and Roland co-founder Ikutaro Kakehashi that led them to the happiest accidents. This is the story of the gear that changed music, and how it almost never happened…

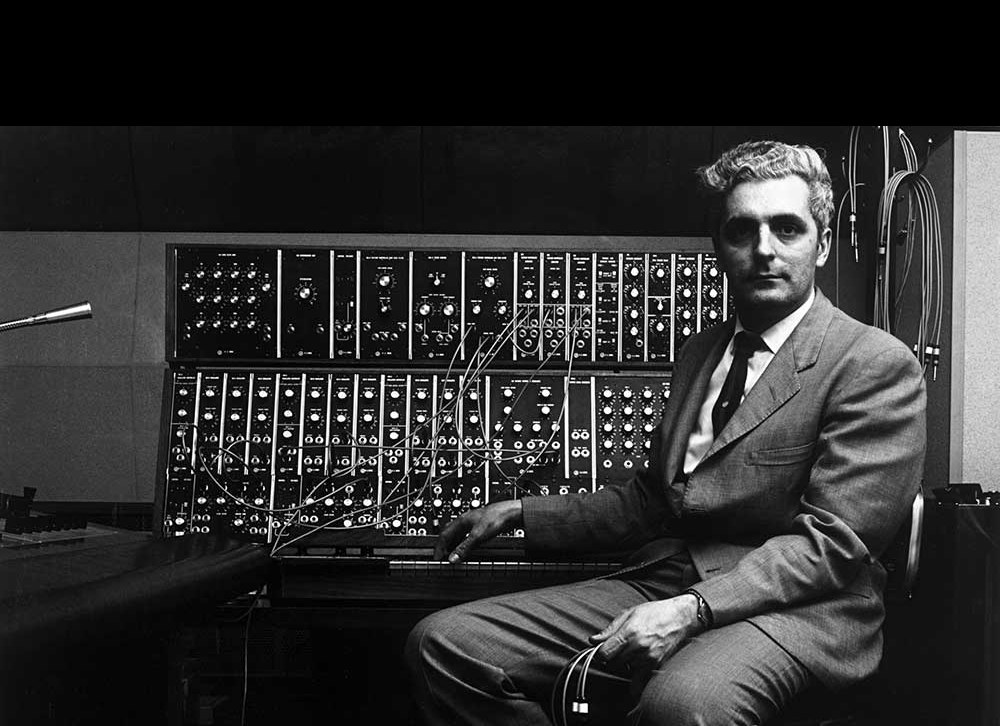

BACK IN MOOG

Though he wasn’t the first to conceive them, Dr Bob Moog (pictured above) is considered the father of synthesizers. The design of his synths and circuits became staples in electronic music, and the Moog name has long been associated with quality and high-end sound.

Undoubtedly his most famous synth and one that set the template for synth design for the decades that followed, the Minimoog Model D scaled down what were huge, expensive and fragile synths into a portable, affordable and playable instrument.

Originally manufacturing guitar amps and a touch-free single tone instrument called a theremin out of New York, Moog began building large format modular synthesizers with complex interfaces and steep learning curves. Sound was created by patching an oscillator to an amplifier, via any combination of sonic manipulators such as envelopes, filters etc. Tones could then be controlled via sequencers, or external keyboards sending signals to determine pitch. Though the sound was impressive, they were out of reach of all but the most affluent and experimental musicians — living mostly in studios and on records by The Doors, Diana Ross (pictured below) & The Supremes and The Monkees.

Moog wanted to introduce a synth that harnessed the sonic power of his large format synths into a portable unit — the Minimoog was born. Unlike the larger modulars that were controlled by a maze of patch chords and dials, the Minimoog was mostly hard-wired, significantly reducing the learning curve and production costs and allowing more traditional musicians to quickly dial up a usable sound. And it’s the sound that’s still talked about today — the Moog filter has become the stuff of legends, known for its liquid sound, capable of silky smooth tones and aggressive bite.

But the renowned filter’s sound was actually completely unintended — it came about as the consequence of a miscalculation by Moog engineer Jim Scott. Scott had inadvertently overdriven the filter by up to 15dB, resulting in a more tough and powerful sound that generated harmonics and cut through speakers. Realising the mistake when the first production run had already began, they decided to leave the design intact and the Minimoog filter sound was born. Its powerful sound and portable, performance-driven design changed the way synths were designed forever.

MOOG IN MUSIC

Though the Minimoog has been used on thousands of records, it’s probably easiest to call to mind its use on Michael Jackson’s ‘Thriller’ album, not just for the music’s popularity but also for the innovative use of the synth on the record. Engineer Bruce Swedien and keyboardist Greg Phillinganes used two modified Minimoogs linked together for many of the album’s signature bass riffs, such as ‘P.Y.T.’ and the title track ‘Thriller’. Producer and musician Kalif also made it his go-to sound on his work with Stevie Wonder, George Benson, Evelyn ‘Champagne’ King and Whitney Houston. Other artists who used the Minimoog include Kraftwerk, Gary Numan, Rick Wakeman, ABBA and many, many more.

MOOG MODERN ALTERNATIVES

Moog recently reintroduced the Model D for the first time since 1981, but it’s not cheap, coming in at over £3,300. If you’re looking for the Minimoog sound on a budget, Arturia’s now somewhat classic Minimoog V is a good option, but Native Instruments’ more recent Monark software synth comes closest to the Minimoog sound in the box. If you’re keen on hardware, German budgeteers Behringer also recently showed off a $400 Minimoog Eurorack module, but no release date has been set.

LINNOVATION

In the late 1970s, Linn Electronics founder and guitarist Roger Linn was unsatisfied with the sound and functionality of drum machines on the market. Largely made up of pre-programmed patterns based around styles like ‘Samba’ and ‘Rock’, they used analogue chips to recreate the sounds of kick-drums, snares and hi-hats, often failing to sound real or powerful. Linn decided to engineer his own drum machine, with rock band Toto’s drummer Jeff Porcaro supposedly inspiring him to use real drum samples over analogue circuitry.

SAMPLE MAGIC

Linn claims to have forgotten who played the samples that were used in the first drum machine to incorporate real drum sounds, but many believe it was Art Wood, a session drummer for the likes of James Brown, Peter Frampton and Tina Turner. The technology was young so the sample time was short, and the quality low, but it was already a huge improvement on what was available.

Its digital sounds and 100 user-defined programs were already unique enough, but Roger Linn added one other feature that defined the LM-1 and went on to become part of his legacy: swing. When considering how to add a human feel to the LM-1, Linn realised that if he delayed every second 16th note, he could create a more natural ‘shuffle’. The LM-1 and the MPC — which Linn later went on to design — are both considered the stuff of legends to thousands of producers around the world.

While ‘swing’ was a deliberate addition to the LM-1, Linn also stumbled on another function that is still used today. “My invention of swing was intentional,” Linn told DJ Mag. “It was my invention of quantisation that was a fortuitous accident. Computer memory was expensive so I initially decided to squeeze 16th-note drum-beats, for example, into one memory location for each 16th note. I also wanted to permit real-time recording of beats.

“When I ran the code and first recorded a beat in real-time, the notes I played were saved into 16th note locations, so they played back on perfect 16th notes, effectively correcting my timing errors. I named this feature ‘Timing Correct’, and all the subsequent products that copied it used the engineering term quantisation.”

Quantise, as it’s usually known, is still used daily in studios throughout the world.

With a mixer and tune control for every sample as well as the aforementioned Shuffle and Timing Correct, LM-1 became a cult classic. Only 500 units were made before the more widespread Linndrum came to market.

Everyone from Phil Collins and Depeche Mode to Vangelis and John Carpenter used the LM-1, but no one defines the sound more than Prince. The thick kick and iconic snare are all over his early records, with ‘When Doves Cry’ defining the drum machine’s unique tuning and swing functions, as well as his own skills as a sonic manipulator. Prince’s infatuation with the machine went a long way to sealing its legacy among musicians and producers, and also gave what in hindsight is a limited unit, a highly sought-after status.

LINNDRUM MODERN ALTERNATIVES

More recently, Roger Linn collaborated with Sequential Circuits founder and co-creator of MIDI Dave Smith on Tempest, an analogue-digital hybrid drum machine. Though it doesn’t sound like the LM-1 per se, it’s a good insight into his forward-thinking design and focus on shuffle and ‘human’ feel. Aside from buying a real LM-1 or Linndrum on the second-hand market, there are many more affordable multi-sampled options from companies like Sample Magic and full kits included with NI’s Maschine and Battery.

ROLAND’S LEGACY

Arguably the most famous drum machines of all time, Roland’s TR-808 and TR-909 went on to define a genre, style and culture and although they were considered commercial failures by Roland, their legacy lives on to this day.

Using entirely analogue sources, the Transistor Rhythm 808 drum machine aimed to allow musicians to program their own drum patterns across a now legendary 16-step sequencer. Its booming bass drum, tight clap, smeared snare and ringing congas were certainly unique but rarely did they sound like the real thing. Even at $4,000 cheaper than its LM-1 competitor, it couldn’t compete with the more realistic sampled sources and the unit went into freefall.

As second-hand prices tumbled, producers in Detroit, Chicago and New York started to snap up the unique unit and began to celebrate its distinctive character, rather than attempting to re-create a traditional drum-kit. Juan Atkins supposedly bought the Motor City’s first 808 for his group Cybotron while in New York, and Afrika Bambaataa defined a genre with the Soulsonic Force track ‘Planet Rock’ (produced by Arthur Baker), which features the 808 heavily.

808 SOUND

What gave the 808 its sizzling, unique sound — and was, once again, unintentional — was a set of faulty transistors used in the machine. Roland’s founder Ikutaro Kakehashi claimed that improvements in circuitry and semiconductor design meant that the 808 is now impossible to truly reconstruct — the integral part simply doesn’t exist.

With 12,000 units made, the 808 ceased production in 1984. Largely cast away by its intended audience, it went on to excite and inspire countless artists, producers, engineers and songwriters for its distinctive tones and remains one of the, if not the most legendary drum machine of all time.

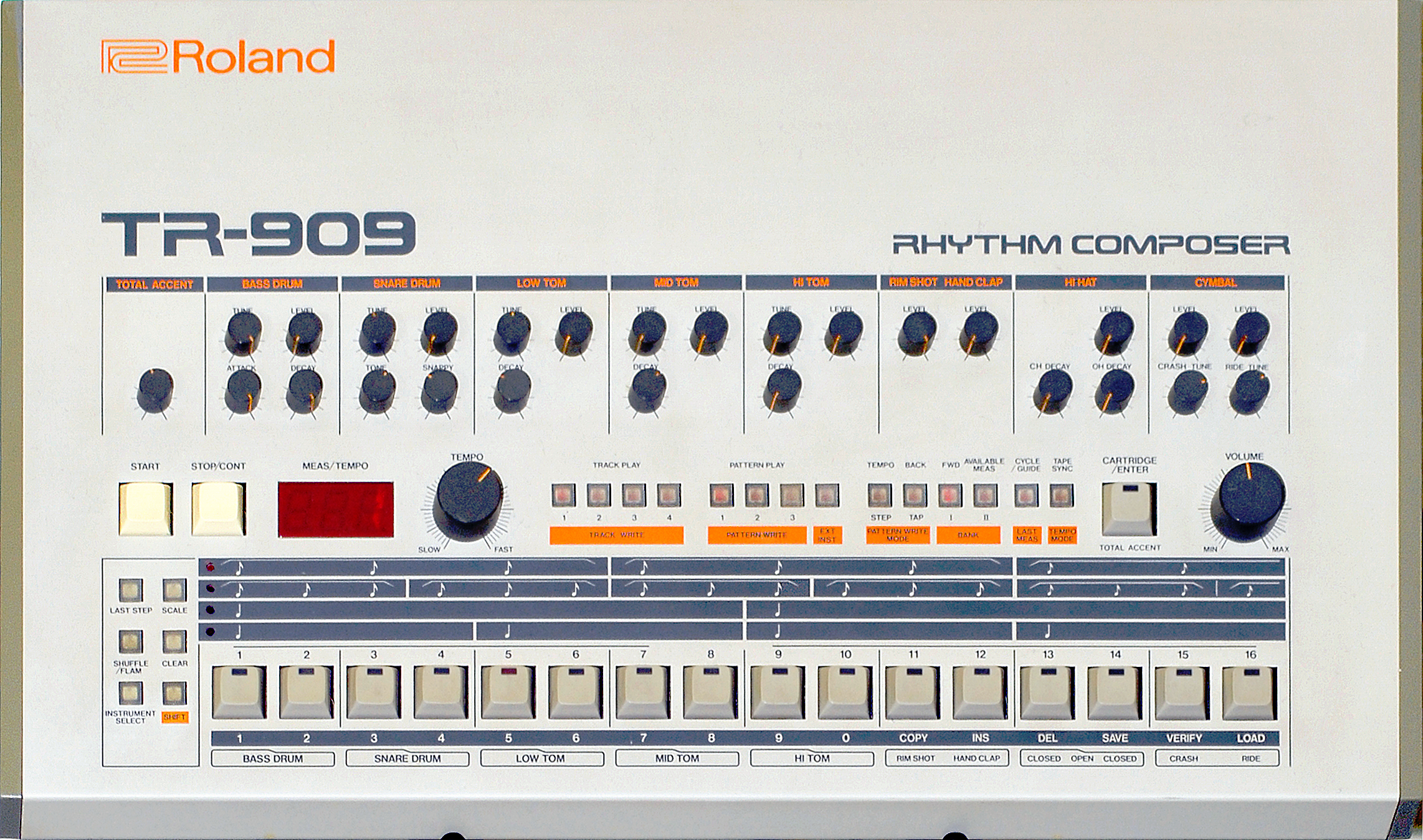

909 TIME

Released the same year that the 808 ceased production, the TR-909 continued the analogue trend with one important exception — Roland struggled to create realistic hi-hat, crash and ride sounds using analogue circuits, so decided to use digital samples just for the cymbals. These cymbals went on to define a genre, not just for their sound but also because of the unique way in which Roland’s TR sequencer worked.

Using the Accent feature — meaning two levels of volume were possible per step, defined by a Total Accent knob — innovative producers were able to create a trademark groove that went on to define the sound of house music.

The 909 was also one of the first drum machines to adopt the newly formed MIDI standard, meaning external control and sync was much easier to achieve. Its sequencer allowed up to 96 rhythm patterns that could be chained together as ‘songs’. Even though these extra features brought the 909 closer to its competition, once again the target market shunned the unit and after only a year in production, Roland brought it off the assembly line.

There was a social shift that inadvertently led to the success of the 909 as an iconic house music staple. As disco was driven back to the underground in a post-‘Disco Sucks’ society, innovators in Chicago and Detroit turned to more affordable ways to make their music and add drums to their tracks. With the 909 being regarded as the ‘toughest’ drum machine on the market, artists like Ron Hardy and Frankie Knuckles began to incorporate it into their music and even their DJ sets, playing the drum machine over disco records in the booth. In Detroit, the Belleville Three — Juan Atkins, Kevin Saunderson and Derrick May — were using the 909 to craft a whole new style, a sound that became almost inseparable from early techno.

Both the 808 and the 909’s impact on electronic music could never have been predicted in the labs of Roland Japan, but they had an immeasurable impact on dance music culture and history.

HEAR THE GEAR

Some early examples of the 909 in action include Mr Fingers ‘Can You Feel It’, where the unit’s sampled ride cymbal can be clearly heard. Hardrive’s ‘Deep Inside’, MK’s ‘Burnin’ and Daft Punk’s not so subtly titled ‘Revolution 909’ (pictured above) all borrow heavily from the iconic machine. For the TR-808, Marvin Gaye’s ‘Sexual Healing’ is undoubtedly the most famous example in pop culture, while more recent hip-hop and trap often use 808 as a bassline, re-sampling and pitching the subby kick.

“As for the TB-303’s ability to re-create a traditional bass guitar sound to help guitarists practice — well, we all know what happened there!”

808 or 909 MODERN ALTERNATIVES

If you’re looking for the 808 or 909 sound for the modern studio — and can’t afford second-hand prices — Roland’s recently released TR-8 features both classic units in one modern interface. It’s already been spotted in the studio and on stage with the likes of Disclosure, KiNK and Mathew Jonson. More recently still, Roland released the TR-09, a more direct clone of the 909 in miniature form.

If you’re looking for an in-the-box solution, there are countless options including full multi-samples from Goldbaby and Sample Magic right down to sythesised emulations from D16 and Softube.

THE BIRTH OF SAMPLING

An iconic, innovative and truly unique instrument, the Fairlight CMI was designed by Peter Vogel and Kim Ryrie (pictured below) in 1979. It allowed users to record in and almost immediately play back and manipulate sounds they’d just mic’d up. It was the birth of sampling; a concept that completely changed the way music was made. But once again, this revolution was never the intention when the instrument was first designed.

What became the Fairlight started life as a project to build a digitally-controlled analogue synth. Attempting to create a more realistic sound for their synth, Vogel decided to record a piano sound from the radio to study its harmonics. When he re-triggered the sound at different pitches, he realised it sounded a lot more like a real piano than their attempts using digital synthesis. The duo quickly abandoned the synthesis side of the project, and the Fairlight was born.

SAMPLING SORROWS

Despite the innovations, neither Vogel nor Ryrie were particularly proud of using ‘real’ sounds in the Fairlight, and saw it as ‘cheating’ in their attempt to create a realistic-sounding digital synth. The Musicians’ Union weren’t impressed either, and campaigned against the Fairlight after it appeared on BBC’s futuristic show Tomorrow’s World, calling its sampling capabilities a “legal threat” to its members. It was the beginning of a long and complicated legal history for sampling.

Regardless of the designers’ intentions and its somewhat frosty reception in certain parts of the music industry, the concept was revolutionary. It came at a price to match though, with the first instance of the Fairlight costing £12,000 — about £63,000 in today’s money.

Nevertheless, forward-thinking producers with big enough wallets jumped at the chance to own the futuristic sampler and sequencer, its touch-screen and light pen controller adding to the space-age style. Peter Gabriel became a champion of the Fairlight, even forming a company to distribute the sampler in the UK. It went on to be owned by the likes of Stevie Wonder, Trevor Horn, Kate Bush, Herbie Hancock and Todd Rundgren.

HEAR THE GEAR

Though the unit only had one second of sampling time, Vogel says this is a creative limitation, forcing producers to work within the limits of the machine. It did mean that short, percussive sounds were more popular — you can hear the Fairlight working its magic on Art Of Noise ‘Moments In Love’, Pet Shop Boys ‘Love Comes Quickly’ and Peter Gabriel’s ‘Sledgehammer’.

Later versions of the Fairlight introduced even more innovative concepts that are still around today including Page R, which allowed users to sequence and program sounds, layered on top of each other — not unlike the MIDI clips we program in our DAWs today.

CMII MODERN ALTERNATIVES

The cheapest and easiest way to get your hands on the Fairlight sound is via the official iOS app ‘Peter Vogel CMI’ — available on the App Store. Touch-screen, just like its grandad, it features all the original sounds from the legendary CMI II — it even has a Page R section. Alternatively, try UVI’s Darklight, a multi-sampled Fairlight instrument VST.

ALTERNATIVE HISTORY

Though these machines and their creators rightly go down as legendary gear and designers, they all had a common thread — chance. Whether it was the Minimoog’s over-driven filter, the LM-1’s ‘quantise’ creation, the 808 and the 909 accidentally defining house and techno or the Fairlight’s sampling discovery, they all accidentally changed the way electronic music is made.

More importantly, it was their initial forward-thinking designs that led to the happy accidents we now take for granted. As long as electronic music retains its thirst for innovation, new legends will continue to be born.

SOURCE: DJ MAG

Comment here