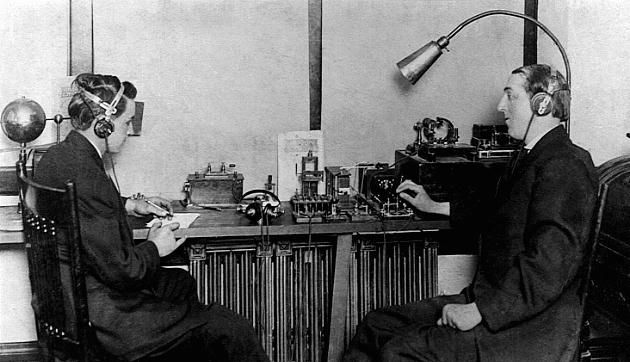

The term “disc jockey” first appeared in 1935, about two decades after Reginald Fessenden played George Frideric Handel’s Largo from the opera Serse in 1906, the first radio broadcast of recorded music in history. Technically, DJing entails the playing of multiple records in succession, so the honor of being the world’s first goes to Ray Newby, assistant to radio pioneer Charles “Doc” Herrold who founded the Herrold College of Engineering and Wireless in San Jose, Calif. Radio was new territory at the time and had no regulations for broadcasting.

The term “disc jockey” first appeared in 1935, about two decades after Reginald Fessenden played George Frideric Handel’s Largo from the opera Serse in 1906, the first radio broadcast of recorded music in history. Technically, DJing entails the playing of multiple records in succession, so the honor of being the world’s first goes to Ray Newby, assistant to radio pioneer Charles “Doc” Herrold who founded the Herrold College of Engineering and Wireless in San Jose, Calif. Radio was new territory at the time and had no regulations for broadcasting.

The school was built primarily for training operators for ships, but at the age of 16 Newby got the blessing from Doc to play continuous music on air, many of which were Enrico Caruso records, the Italian operatic tenor who became a superstar thanks to the popularity of prolific recording career:

“We used popular records at that time, mainly Caruso records, because they were very good and loud; we needed a boost. We started on an experimental basis and then, because this is novel, we stayed on schedule continually without leaving the air at any time from that time on except for a very short time during World War I, when the government required us to move the antenna. Most of our programming was records, I’ll admit, but of course we gave out news as we could obtain it. (“I’ve Got a Secret” 1965)

Radio at the time was a mixture of news, sports and radio drama in addition to live music. This changed in 1927 thanks to Christopher Stone, who was the editor of a classical music magazine called The Gramophone. Stone had the idea of a program dedicated solely to recorded music, convincing a skeptical BBC to launch the program July 7 to great success. Contrasting with radio’s formal presentation, Stone delivered in a friendly manner that appealed to audiences listening to records for the first time, making him the first DJ to achieve star status. Before leaving for pirate radio, pioneer Radio Luxembourg (and getting blacklist by BBC in the process), Stone even developed his own dual turntable setup almost two decades before Jimmy Savile.

Walter Winchell would coin the term “disc jockey” in 1935, describing Martin Block’s “Make Believe Ballroom,” the first American record show to become a hit with radio audiences. Block was an announcer at WNEW in New York when the Lindbergh kidnapping hit the news. As listeners waited for updates, Block began playing records to keep people entertained, mimicking the feel of a live concert broadcast. His personal style felt more like a conversation than a theater announcer, foreshadowing the rise of radio personalities in the following decades. As the show went on to become nationally syndicated, gramophone technology continued to advance and move into more living rooms.

Walter Winchell would coin the term “disc jockey” in 1935, describing Martin Block’s “Make Believe Ballroom,” the first American record show to become a hit with radio audiences. Block was an announcer at WNEW in New York when the Lindbergh kidnapping hit the news. As listeners waited for updates, Block began playing records to keep people entertained, mimicking the feel of a live concert broadcast. His personal style felt more like a conversation than a theater announcer, foreshadowing the rise of radio personalities in the following decades. As the show went on to become nationally syndicated, gramophone technology continued to advance and move into more living rooms.

Prior to the 20th century, gramophone records were produced with no standardized rpm or size. Berliner sold 7-inch discs that were “about 70 rpm,” but the introduction of a governor (speed regulator) in 1897 enabled uniform recordings, eventually leading to the 78 rpm standard. There wasn’t any reason for the industry to adopt this speed; records were labeled with whatever arbitrary speed was chosen by the recording machine and 78 became the most common format before the introduction of the LP.

Vinyl, long-playing records marked a turning point in recorded music. Older shellac records were brittle and noisy in addition to only providing less than five minutes of recording time on each side. Radio transcription discs were the first records to use vinyl (then called vinylite), and the U.S. government later contracted several record companies to produce V-Discs, which were vinyl 78s with special recordings for soldiers overseas in World War II. These rare discs feature recordings from top artists of the time like Frank Sinatra and Billie Holiday, though it was illegal to use them for commercial purposes before becoming collectors’ pieces today.

Columbia Records issued the first contemporary LPs in 1948, producing discs at 33 1/3 rpm that competed with RCA Victor’s 45 rpm albums released shortly after. With 26 minutes of music per side, 12-inch 45s eventually made way for the Album Era, when artists took advantage of the long format to produce iconic concept records, most notably The Beatles’ “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band” (1967). Long-playing records became the most popular format as transistor phonographs entered millions of homes, while DJs took advantage of the higher fidelity and durability the new technology brought.

Columbia Records issued the first contemporary LPs in 1948, producing discs at 33 1/3 rpm that competed with RCA Victor’s 45 rpm albums released shortly after. With 26 minutes of music per side, 12-inch 45s eventually made way for the Album Era, when artists took advantage of the long format to produce iconic concept records, most notably The Beatles’ “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band” (1967). Long-playing records became the most popular format as transistor phonographs entered millions of homes, while DJs took advantage of the higher fidelity and durability the new technology brought.

The post-war period gave rise to the radio personality, disc jockeys who were followed for their unique taste in music and responsible for introducing new sounds to the public. Alan Freed coined the phrase “rock and roll” at WJW Cleveland as well as presenting artists across color lines in the early 1950s. Popular music as a cultural fixture developed out of this new format as modern DJing began to take form with radio DJs hosting “sock hops” or “platter parties,” often with a live drummer to fill in the time between songs.

The post-war period gave rise to the radio personality, disc jockeys who were followed for their unique taste in music and responsible for introducing new sounds to the public. Alan Freed coined the phrase “rock and roll” at WJW Cleveland as well as presenting artists across color lines in the early 1950s. Popular music as a cultural fixture developed out of this new format as modern DJing began to take form with radio DJs hosting “sock hops” or “platter parties,” often with a live drummer to fill in the time between songs.

In Jamaica, sound systems playing American R&B became dominant in Kingston, eventually adapting their sound to ska and reggae with custom-built rigs that could play very loud bass frequencies. In addition to the DJ, selectors would be responsible for choosing records while a vocalist would “toast” the audience. Not to be confused with rapping, toasting involves rhythmic chanting originating from West African oral traditions.

Sound system culture would go on to have an influence on a number of genres, most notably the Jamaican-born “father of hip hop,” DJ Kool Herc introduced beat juggling to the Bronx in 1973.

Isolating breaks was already popular with dub music, but Kool Herc adapted the technique to American funk and soul, giving rise to hip hop with rappers continuing the Jamaican toasting tradition.

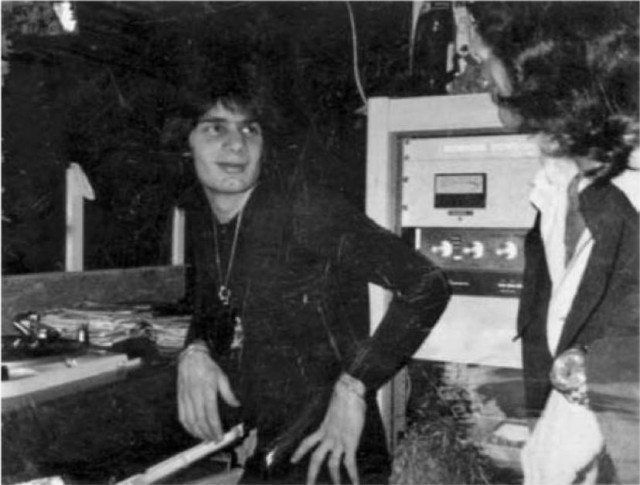

Prior to this, Francis Grasso developing some of the most basic DJ techniques we use today while playing at New York’s Sanctuary club. In 1969, Grasso used the practice of clip-cueing (already popular in radio) to beatmatch tracks together, on Thorens turntables no less, which were high-end at the time but much less reliable than Technics.

Grasso’s mixes were particularly impressive, considering this was on live drummers and he was capable of crafting long blends with careful attention. The man is also known for changing the game in music selection. DJing was most often played to the audience off the popular charts, but Grasso went against the mold by choosing a variety of styles, playing close attention to the mood and musical narrative.

Grasso’s mixes were particularly impressive, considering this was on live drummers and he was capable of crafting long blends with careful attention. The man is also known for changing the game in music selection. DJing was most often played to the audience off the popular charts, but Grasso went against the mold by choosing a variety of styles, playing close attention to the mood and musical narrative.

In 1974, DJing would get its iconic instrument with Technics’ release of the SL-1200, a special endeavor by Matsushita to create a high quality and reliable record player. The turntable would go on to become the industry standard thanks to its high torque, low flutter magnetic drive and heavy insulation against acoustic feedback, not to mention that they are very durable. While Technics have always been popular in the DJ community, the rise of digital music, CDJs and MIDI technology lost the company sales.

![Joey B – ‘La Familia’ [Music Video]](https://ghanadjawards.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/maxresdefault.jpg)

Comment here